You're lying in bed, windows open on a warm night. That familiar, rhythmic chirping starts up. Is it one cricket or a dozen? What about that loud, buzzing drone from the trees this afternoon—same insect? Most of us hear insect sounds every day but know shockingly little about them. I spent a decade recording wildlife sounds, and insects were the most frustrating, then the most fascinating subject. Everyone talks about bird calls, but the insect orchestra is more complex, more accessible, and honestly, more useful in our daily lives.

This isn't just an academic curiosity. Knowing how to identify insect sounds can turn a sleepless night into a relaxing soundscape, a hike into a detective game, or a smartphone into a field recording studio. Let's cut through the noise.

What's Buzzing Inside?

How Insects Actually Make Those Noises

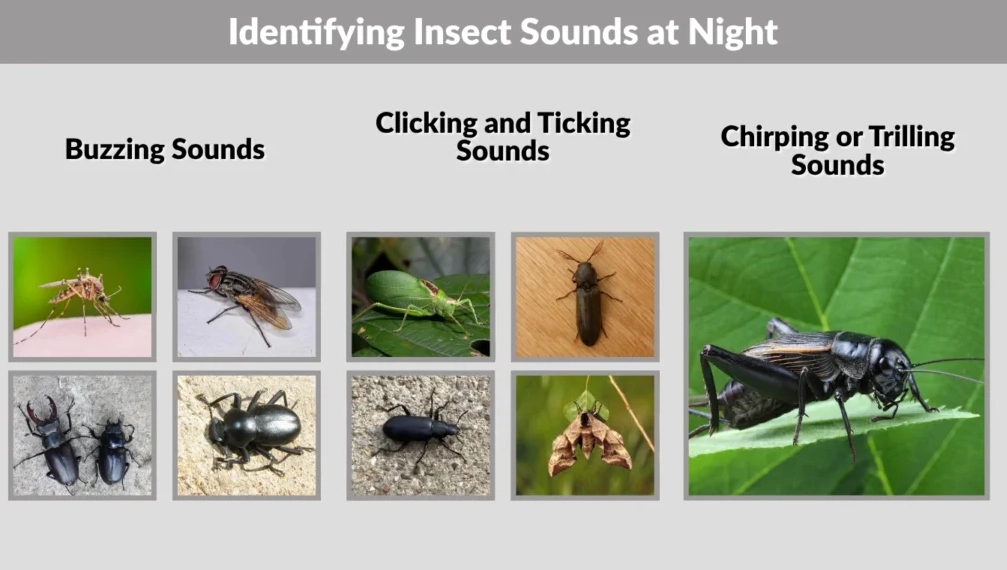

It's not a voice. Insects don't have vocal cords. The sounds come from specialized body parts being rubbed, vibrated, or snapped together. Think of it as mechanical music.

Stridulation is the big one. It's like a fiddle and bow. A cricket rubs a sharp scraper on one wing against a file-like ridge on the other. Katydids do something similar. The speed and structure of the file determine the chirp's pitch and rhythm.

Tymbals are how cicadas achieve that deafening buzz. They have paired, ribbed membranes on their abdomen. Powerful muscles buckle these tymbals in and out hundreds of times a second. It's an internal drum kit, and it's incredibly efficient—nearly all the energy becomes sound. That's why a tiny cicada can drown out a lawnmower.

Then there's vibration. Many insects, like certain beetles and flies, make sounds by vibrating a specific body part against the ground or a plant stem. The sound travels through the material, not the air. You often feel these sounds more than you hear them.

A Quick Note on Temperature

Here's a bit of practical trivia most guides miss: Cricket chirping rate is a decent thermometer. Dolbear's Law states you can approximate the temperature in Fahrenheit by counting the number of chirps a snowy tree cricket makes in 14 seconds, then adding 40. It's not lab-grade, but on a quiet evening, it's a fun party trick that connects you directly to the insect's physiology. Try it.

Who's Making That Sound? A Field Guide to Common Insect Calls

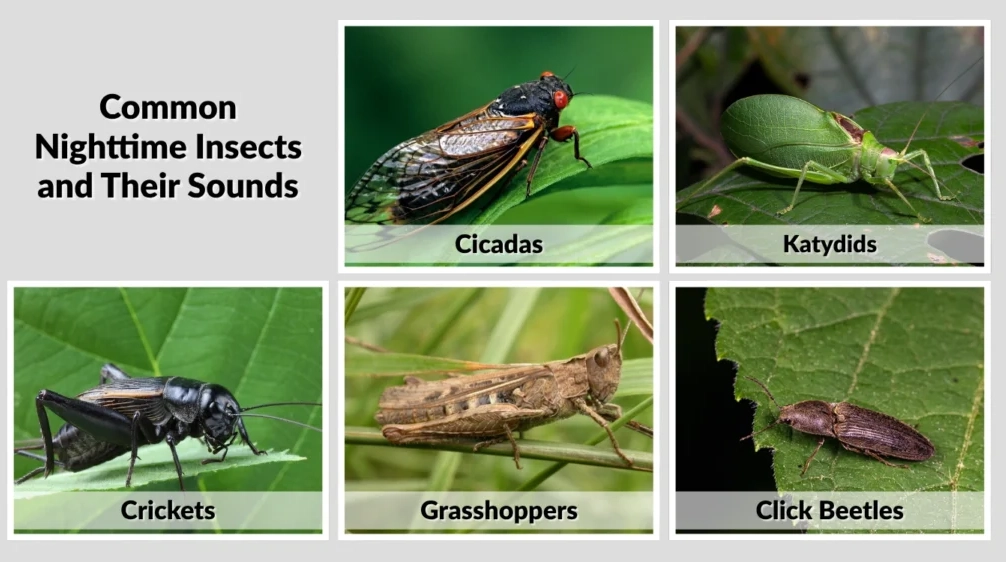

Let's match the sound to the source. This table covers the usual suspects you'll encounter in North America and many temperate regions.

| Insect | Sound Description | When & Where You'll Hear It | Common Confusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Cricket | Loud, musical, rhythmic chirps. A steady pulse. | Night, late summer/fall. Ground level in grass, under debris. | Confused with tree crickets (softer) or frogs. |

| Katydid (True) | Harsh, loud "Katy-did, Katy-didn't" or a slow, rhythmic rasp. | Night, midsummer. High in deciduous trees and shrubs. | Often mistaken for a very loud, grating cricket. |

| Annual Cicada | A long, continuous, buzzing/wavering drone that rises and falls in intensity. | Daytime, peak summer. High in trees. | People think it's an electrical box humming or a giant fly. |

| Periodical Cicada | A loud, chaotic, oceanic chorus of buzzing, clicking, and whirring. | Daytime, during emergence years (e.g., 2024, 2025). Forests. | Unmistakable in mass, but individuals sound like a softer buzz. |

| Grasshopper | Short, soft buzzing or ticking sounds, often in flight. | Daytime, late summer. Grassy fields. | Can be missed entirely; sounds like a tiny rattle. |

| Bumblebee | A steady, mid-pitched buzz from wingbeats. | Daytime, near flowers. Close proximity. | The classic "buzz" we associate with all bees. |

| Mosquito | A high-pitched whine near your ear (female wingbeats). | Dusk and night, close to your head. | Annoyingly distinctive. |

The biggest mistake beginners make? Assuming all nighttime chirping is from the same insect. Next time, really listen. Is it a clean, metallic chirp (likely a tree cricket) or a rougher, more guttural scrape (likely a katydid)? The location gives it away too. Sound from the grass is a ground cricket. Sound from 20 feet up in an oak tree is almost certainly a katydid.

How to Record Insect Sounds (Without Fancy Gear)

You don't need a $2000 microphone. I've gotten my cleanest insect recordings with surprisingly simple setups. The goal is to capture the sound, not the rustle of every leaf you step on.

- Your Smartphone is a Start: Modern phones have decent mics. Use an app that records in WAV format (like Voice Memos on iOS or a third-party app like RecForge II on Android). This preserves more quality than a compressed MP3. The key is to get close and hold still. Prop the phone against a rock or log to avoid handling noise.

- The Lavalier Mic Upgrade: For under $30, a lavalier (lapel) microphone plugged into your phone is a game-changer. You can place it on a leaf near the insect, run the cable back, and control the recording from a distance. This isolates the sound beautifully.

- Wind is Your Enemy: It will ruin everything. Even a light breeze sounds like a hurricane on a sensitive recording. Record on still nights. If you must record with a breeze, position your body or a notebook (carefully) as a windbreak between the mic and the wind direction.

- Get Low and Listen: Crickets and grasshoppers are at ground level. Get your microphone down there. For tree-dwellers like cicadas, you're often better off recording from a slight distance to get a more balanced, less piercing tone.

My first "professional" insect recording was a disaster. I hiked for miles with heavy gear to find a rare katydid. I found it, set up my expensive shotgun mic... and captured 20 minutes of perfect audio dominated by the crunch of my own knees settling into position. Lesson learned: movement is the second biggest enemy. Set your gain, hit record, and freeze.

Using Insect Sounds for Sleep, Focus, and Creativity

This is where insect sounds move from a hobby to a practical tool. Not all nature sounds are created equal.

The steady, rhythmic chirping of crickets or the low drone of a distant cicada swarm works for sleep and focus because of a principle called stochastic resonance. Basically, a consistent, non-threatening background noise can help your brain filter out more jarring, irregular interruptions (a car door slamming, a pipe clanking). It provides acoustic masking.

But you have to choose wisely. That loud, buzzing fly trying to escape your window? That's stressful. The erratic, sharp clicks of some beetles? Not soothing.

For Sleep: Look for recordings labeled "cricket chorus," "summer night sounds," or "forest ambiance." The best ones have a deep, low-frequency rumble with chirping layered on top. They should loop seamlessly. I avoid ones with sudden bird calls or water sounds mixed in, as the variation can be distracting.

For Focus (Deep Work): I personally use a recording I made of a single field cricket. Its metronomic chirp is less engaging than music with lyrics, but more organic than white noise. It creates a cognitive "cone of silence." Websites like the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are treasure troves of pure, high-quality field recordings you can use for this.

Beyond the Background: Insects in Music and Sound Art

Composers have been fascinated by insect sounds for centuries. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote a "Flight of the Bumblebee." But modern technology lets us use the actual sounds.

Bioacoustics is the scientific study, but musique concrète and electronic artists use insect recordings as raw material. A composer might slow down a cicada drone 100x, revealing harmonic structures you'd never hear otherwise, and layer it into a soundtrack. I know a producer who samples the click of a beetle's mandibles and uses it as a percussive hi-hat.

You can try this. Take a short recording of a cricket chirp. Load it into a free audio editor like Audacity. Slow it down drastically. Suddenly, a single chirp becomes a eerie, sweeping laser-like sound that lasts for seconds. Speed it up, and it becomes a metallic ping. It's a reminder that this sound world operates on a timescale we usually ignore.

Your Insect Sound Questions, Answered

Let's tackle the specific things people really want to know.

The world of insect sounds is right outside. You don't need to go to a national park. Start tonight. Open your window, or step into your yard. Just listen. Try to pick out one rhythm from the chorus. Is it fast or slow? High or low? That's the first step into a much larger world—one that's been playing a soundtrack to our planet for millions of years, long before we arrived to listen.

The world of insect sounds is right outside. You don't need to go to a national park. Start tonight. Open your window, or step into your yard. Just listen. Try to pick out one rhythm from the chorus. Is it fast or slow? High or low? That's the first step into a much larger world—one that's been playing a soundtrack to our planet for millions of years, long before we arrived to listen.