Quick Navigation

- What Exactly Is an Aphid, Anyway?

- Spotting the Enemy: How to Identify an Aphid Infestation

- The Real Cost: What Kind of Damage Do Aphids Cause?

- Meet the Usual Suspects: Common Types of Garden Aphids

- Your Action Plan: How to Control and Get Rid of Aphids

- Answering Your Burning Aphid Questions

- Wrapping It Up: Living With (and Managing) Aphids

You know the feeling. You're out admiring your roses, your kale, or your precious young fruit trees, and there they are. Clustered on the tender new growth, looking like a tiny, moving carpet. Aphids. At first, you might ignore them. How much damage can such tiny insects do, right? I made that mistake once, and let me tell you, I spent the rest of the summer fighting a losing battle against sticky leaves and stunted plants. It was a mess.

This guide is everything I wish I'd known back then. We're not just going to talk about how to get rid of aphids—we're going to understand them. Because honestly, the best way to win a fight is to know your enemy. And aphids, for all their small size, are fascinating and formidable opponents in the garden.

What Exactly Is an Aphid, Anyway?

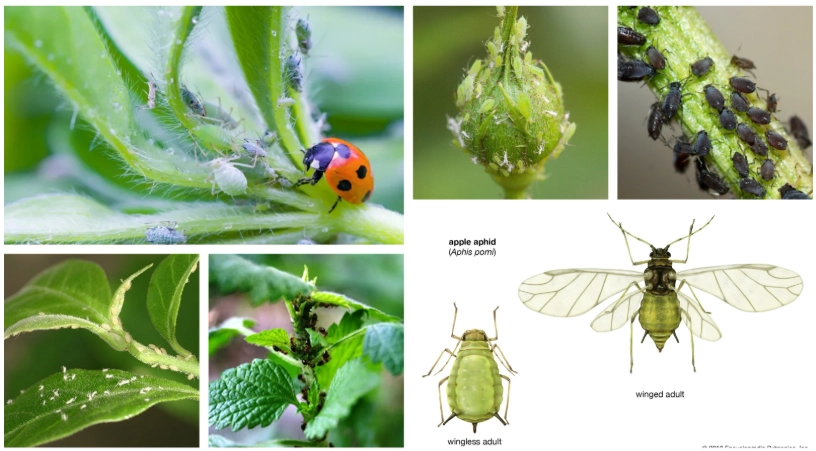

If you're going to deal with them, you should know what you're looking at. Aphids are small, soft-bodied insects belonging to the superfamily Aphidoidea. There are thousands of species—something like 5,000 worldwide. The most common one you'll see in your garden is probably the green peach aphid, but there are also black bean aphids, woolly apple aphids (they look like they have little white fluff on them), and many more.

Their life cycle is... weird. And it explains why they multiply so fast. In spring, wingless female aphids hatch from eggs and start giving birth to live female clones. No males needed. This is called parthenogenesis. These daughters mature in about a week and start producing their own clones. You see how this gets out of hand quickly? When the colony gets too crowded or the host plant starts to decline, they produce winged females that fly off to start new colonies. In the fall, males are finally produced to mate with females who lay the overwintering eggs.

It's a brutally efficient system. And their mouthparts are perfectly designed for it. They have piercing-sucking mouthparts called stylets. They pierce the plant's phloem—the sugary sap pipeline—and just suck it out. It's like tapping a maple tree, but for the aphid, it's an all-you-can-eat buffet.

Spotting the Enemy: How to Identify an Aphid Infestation

You don't need a magnifying glass, but it helps. Here’s what to look for, beyond just the bugs themselves.

The Aphids Themselves

Look for small (1-3 mm), pear-shaped insects. They're often green, but can be black, brown, yellow, pink, or even white (if they're the woolly type). They tend to crowd together on the undersides of leaves and on new, soft stem growth. That's the sweet spot for them—tender tissue is easier to pierce.

The Secondary Signs (Often More Noticeable)

- Honeydew: This is the big one. Aphids excrete a sticky, sugary substance called honeydew. If your leaves feel sticky or look shiny, or if you notice a black, sooty mold starting to grow on them, you've got honeydew. That mold is a fungus that grows on the sugar, and it can block sunlight from reaching the leaf.

- Distorted Growth: Leaves may curl, cup, or become twisted. New growth can look stunted and puckered. This is a direct reaction to the aphid's feeding and sometimes their saliva.

- Ant Activity: Ants love honeydew. They'll actually "farm" aphids, protecting them from predators in exchange for this sweet treat. If you see a trail of ants marching up and down your plant, look for aphids at the top.

What plants are most at risk? Honestly, most of them. But they have favorites. Roses, fruit trees (especially young ones), peppers, kale, cabbage, tomatoes, melons, and beans are common targets. They also love ornamental plants like nasturtiums and milkweed.

The Real Cost: What Kind of Damage Do Aphids Cause?

It's easy to underestimate them. They're so small. But the damage adds up, and it comes in a few forms.

Direct Damage: By sucking out the phloem sap, they're stealing the plant's energy—the sugars it made through photosynthesis to fuel its own growth. A heavy infestation can literally starve a plant, especially a young one. The leaf distortion also reduces the plant's ability to photosynthesize effectively.

Indirect Damage (The Honeydew & Sooty Mold Problem): This is often more unsightly than deadly, but it's a real pain. The sooty mold itself doesn't infect the plant, but a thick coating can significantly reduce light absorption. I've seen entire branches of a crepe myrtle turn black. It washes off with soapy water, but it's a chore.

The Virus Vector Problem (The Silent Threat): This is, in my opinion, the most serious issue. Many aphid species are vectors for plant viruses. As they move from plant to plant, piercing and sucking, they can transmit diseases like cucumber mosaic virus, potato virus Y, and various mosaic viruses. You can't cure a viral infection in a plant. If an aphid infests your crop and only causes some leaf curl, you might get a reduced harvest. If it brings a virus, you might lose the entire plant.

Meet the Usual Suspects: Common Types of Garden Aphids

Knowing which aphid you're dealing with can sometimes point you to their favorite hosts or life cycle. Here's a quick rundown of the ones you're most likely to meet.

| Aphid Type | Color & Appearance | Favorite Host Plants | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Peach Aphid | Pale yellow-green to green. Small, pear-shaped. | Peppers, potatoes, tomatoes, lettuce, stone fruits, cabbage family. | The most common and widespread. A major virus vector. |

| Black Bean Aphid | Dark olive green to black, often with a white waxy dusting. | Broad beans, nasturtiums, dahlias, poppies, sugar beets. | Forms very dense, obvious colonies. Loves tender shoot tips. |

| Woolly Apple Aphid | Purplish-brown but covered in white, wool-like waxy filaments. | Apple, pear, elm, hawthorn trees. | Causes galls (knobby swellings) on roots and branches. Hard to miss. |

| Melon/Cotton Aphid | Color varies wildly from yellow to dark green to black. | Cucumbers, melons, squash, cotton, citrus. | Extremely prolific. Can build huge populations in hot weather. |

| Rose Aphid | Green or pinkish. Larger than some other species. | Roses (surprise!), but also apples and pears. | Classic garden pest. Loves the buds and new growth of rose bushes. |

See? They're not all just "green bugs." That woolly apple aphid looks like something from a sci-fi movie. Identifying them precisely isn't always necessary for treatment, but it helps you understand their habits. For really detailed taxonomic information, entomology resources from institutions like the University of Minnesota Department of Entomology are invaluable.

Your Action Plan: How to Control and Get Rid of Aphids

Okay, you've found them. Now what? Don't immediately reach for the chemical spray can. That should be your last resort, not your first. You'll kill all the good bugs too, and you might just make the problem worse in the long run. Here's a tiered approach that actually works.

Step 1: Prevention (The Best Medicine)

Stop the problem before it starts. Healthy plants are less susceptible. Give them the right amount of water, sunlight, and nutrients. Avoid over-fertilizing with high-nitrogen fertilizers, as the lush, soft growth that results is aphid candy. Encourage biodiversity in your garden. A monoculture is a target; a mixed planting is a confusing maze for pests.

Step 2: Physical & Mechanical Control (The Immediate Response)

For a light infestation, this is often all you need.

- The Blast Method: A strong jet of water from your hose can knock aphids right off the plant. They are soft-bodied and poor climbers. Do this in the morning so the plant has time to dry, reducing disease risk. You'll need to repeat it every couple of days for a while.

- Hand-Picking & Pruning: If the infestation is localized to a few shoots or leaves, just pinch them off and drop them into a bucket of soapy water. It's gross but effective.

- Yellow Sticky Traps: These catch the winged aphids that are looking to start new colonies. They won't control an existing infestation but can help monitor and reduce spread.

I've saved many a pepper plant just by turning the hose on them for three days in a row. It feels silly, but it works.

Step 3: Biological Control (Enlisting an Army)

This is my favorite method. You're using nature against itself. The key is to attract or introduce the natural predators of aphids. Who eats aphids? A lot of creatures.

- Ladybugs (Ladybird Beetles): The classic. Both adults and their spiky, alligator-like larvae are voracious aphid eaters. You can buy them, but they often fly away. It's better to attract them by planting pollen and nectar sources like dill, fennel, and yarrow.

- Lacewings: Their larvae are called "aphid lions" for a reason. They're insatiable. They look like tiny, tan alligators with big pincers.

- Hoverfly Larvae: The adults look like small bees but hover in place. Their legless, maggot-like larvae can consume dozens of aphids per day.

- Parasitic Wasps: Tiny, non-stinging wasps (like *Aphidius* species) lay eggs inside aphids. The wasp larva eats the aphid from the inside out, leaving a hollow, crispy, brown "mummy" on the leaf. If you see these mummies, celebrate! Your natural controls are working.

- Birds: Small birds like chickadees will pick aphids off plants and trees.

For comprehensive lists of beneficial insects and how to attract them, the USDA Agricultural Research Service and state extension services (like University of Minnesota Extension) have fantastic, science-based resources.

Step 4: Organic Sprays & Treatments (When You Need More Firepower)

If physical and biological controls aren't enough, you can escalate to these. They are less harmful to beneficials than synthetic chemicals, but they are still pesticides—use them thoughtfully.

- Insecticidal Soaps: These work by breaking down the aphid's waxy outer coating, causing it to dehydrate. They must contact the insect directly. They have little residual effect and are relatively safe for beneficials once dry. Test on a small part of the plant first to check for sensitivity.

- Neem Oil: This is a multi-purpose fungicide and insecticide derived from the neem tree. It acts as an antifeedant and growth disruptor. It's best used as a preventative or at the very first sign of trouble. It can harm bees if sprayed directly on them, so apply at dawn or dusk when they're not active.

- Horticultural Oils: Similar to neem but typically petroleum- or plant-based. They smother eggs and soft-bodied insects. Good for dormant season application on trees to smother overwintering aphid eggs.

A word of caution: Even "organic" sprays can harm pollinators and beneficial insects if used carelessly. Spot-treat. Don't blanket-spray your whole garden.

Step 5: Chemical Insecticides (The Nuclear Option)

I'm listing this for completeness, but I rarely recommend it for home gardeners. Broad-spectrum insecticides like malathion or permethrin will kill aphids, but they'll also wipe out every ladybug, lacewing, and bee in the area. This can lead to a "pesticide treadmill" where you kill the predators, the aphids come back even stronger (because they reproduce faster than their predators), and you have to spray again and again.

Answering Your Burning Aphid Questions

Wrapping It Up: Living With (and Managing) Aphids

Look, the goal isn't to create an aphid-free garden. That's impossible and frankly, unhealthy. Aphids are a part of the food web. The goal is management. To keep their numbers below a threshold where they cause significant damage or stress to your plants.

It requires a shift in thinking. From "I must eradicate this pest" to "I need to restore balance." Start with the gentlest methods. Encourage the birds and the bugs that do your work for you. Be patient. Sometimes, if you just wait a week or two, the predator population will catch up and solve the problem for you.

My own garden is proof. I haven't used any spray, organic or chemical, on aphids in years. I have them, sure. I'll see a cluster on a rose bud in May. But I also see the ladybug larvae crawling toward it, and the hoverflies hovering nearby. A few leaves might get curled, but the plant thrives. That's a healthy garden. That's the balance you're after.

So the next time you see those tiny green bugs, don't panic. Take a deep breath, identify the problem, and choose the smartest, most sustainable tool for the job. Your garden—and all the life in it—will thank you.