You're in the garden, and there it is. A bug. Maybe it's on your tomato plant, maybe it just landed on your arm. Your brain fires off questions: What is that? Is it going to eat my plants? Should I be worried? Most insect identification guides get lost in scientific jargon. Let's cut through that. Think of this as a detective's manual for the six-legged things in your world. It's less about memorizing Latin names and more about knowing what to look for and where to look it up.

The goal isn't to become an entomologist overnight. It's to move from "weird bug" to "oh, that's a soldier beetle, and it's actually helpful" in a few logical steps.

What's Inside This Guide?

- Why Bother Identifying Insects? (Beyond Curiosity)

- The Gear You Actually Need: From Phone to Hand Lens

- The 5-Step Identification Process in Action

- Meet the Common Cast in Your Garden

- The Quick & Dirty "Friend or Foe" Test

- Top 3 Mistakes Beginners Make (And How to Avoid Them)

- Your Insect ID Questions, Answered

Why Bother Identifying Insects? (Beyond Curiosity)

Sure, curiosity is a great reason. But there are practical ones that hit closer to home.

If you garden, knowing your insects directly impacts your harvest. Spraying a broad-spectrum insecticide because you saw "a bug" is like nuking your entire yard to get rid of ants. You kill the aphid-eating ladybug larvae (which look nothing like the adult ladybugs, by the way) and the pollinating bees. Identification lets you target real pests and protect the allies.

For homeowners, it's about peace of mind. Is that small brown insect a termite, a winged ant, or a harmless beetle? The difference is thousands of dollars in potential damage. Knowing how to spot a bed bug versus a carpet beetle can save you nights of anxiety or prevent a small issue from becoming an infestation.

It changes your perspective. That "mosquito hawk" or "daddy longlegs" flying clumsily around your lamp? It's a crane fly, and it doesn't bite or eat mosquitoes at all. It's mostly harmless. Once you start naming them, the unknown becomes the familiar.

The Gear You Actually Need: From Phone to Hand Lens

You don't need a lab coat. Here’s what's useful, ranked by importance.

Your Smartphone Camera: This is your primary tool. The key is taking usable photos. Get close, ensure good light (use your flash if you have to), and take shots from the top, side, and if you can, the front. A blurry, dark photo of a dot is useless to anyone trying to help you ID it.

A Hand Lens (Jeweler's Loupe): This is the secret weapon. A 10x magnification lens that costs less than a lunch out. It reveals a hidden world: the tiny hairs on a bee's leg, the intricate patterns on a beetle's back, the number of segments on an antenna. This level of detail is often what separates one family of insects from another.

Pro Tip: Don't have a hand lens? Use your phone's camera in video mode and zoom in slowly. You can often see finer details on the screen than in a quick snapshot.

Digital Field Guides & Apps: Books are great, but apps are faster. I lean heavily on iNaturalist. You upload your photo, and its AI suggests an ID. The real power comes from the community of naturalists and experts who can confirm or correct it. It's like having a global bug ID network in your pocket. Seek by iNaturalist is great for instant, gamified ID without uploading. For North America, the BugGuide website is an unparalleled, expert-curated resource.

A Small, Clear Container: A pill bottle or a glass jar. Sometimes you need to gently contain the insect to get a good look or photo, especially if it's fast-moving. Always release it where you found it after.

The 5-Step Identification Process in Action

Let's walk through a real scenario. You find a shiny, roundish insect on a sunflower stem.

Step 1: The Big Picture. Don't zoom in yet. Where is it? (On a plant, in soil, on water?) What is it doing? (Eating, flying, mating?) Is it alone or in a group? Habitat and behavior are massive clues. A bug on milkweed is likely a milkweed specialist, like a monarch caterpillar or a milkweed bug.

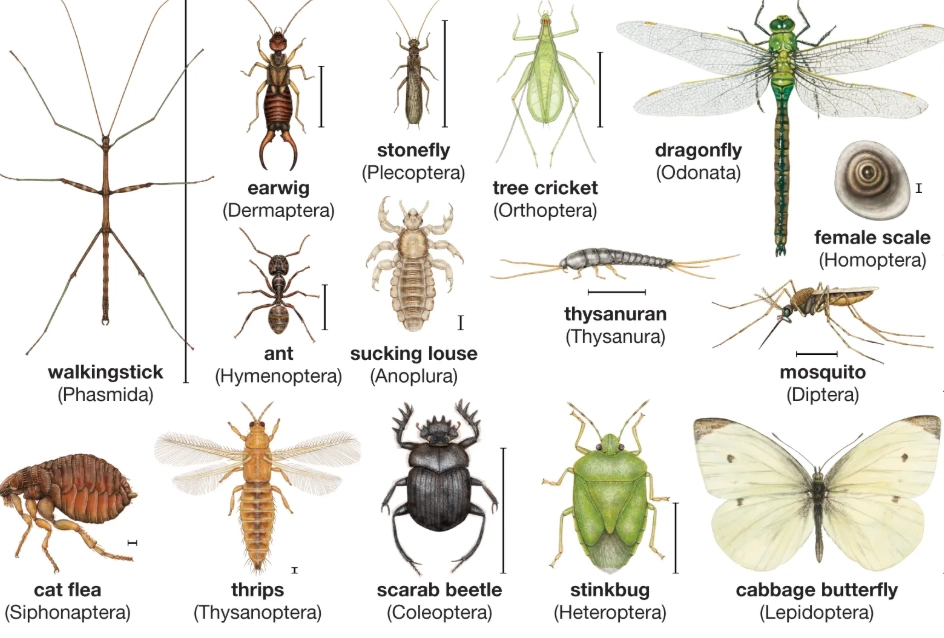

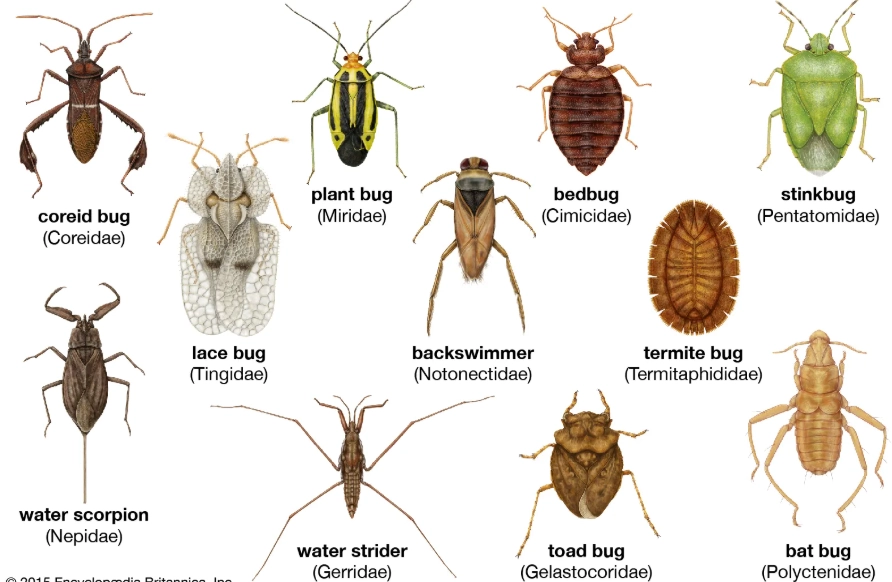

Step 2: The Body Blueprint. This is about major architecture.

- Wings: How many? Two? Four? Are they hard like a shell (beetles), membranous (bees, flies), or scaled (butterflies)? Are they held flat, roof-like, or straight out?

- Body Parts: Can you clearly see a head, thorax (where legs/wings attach), and abdomen? Or is it all fused together?

- Mouthparts: Can you see a long "beak" (like a stink bug) or chewing mandibles (like a beetle)? This tells you how it eats.

Step 3: Zoom In With Your Lens. Now get detailed.

- Antennae: Thread-like? Clubbed? Feathery? How long are they compared to the body?

- Legs: Are they all similar? Are the front legs modified for grabbing (like a praying mantis)? Are they hairy?

- Eyes: Large and bulging? Small? Multiple tiny eyes (simple eyes) in addition to big compound ones?

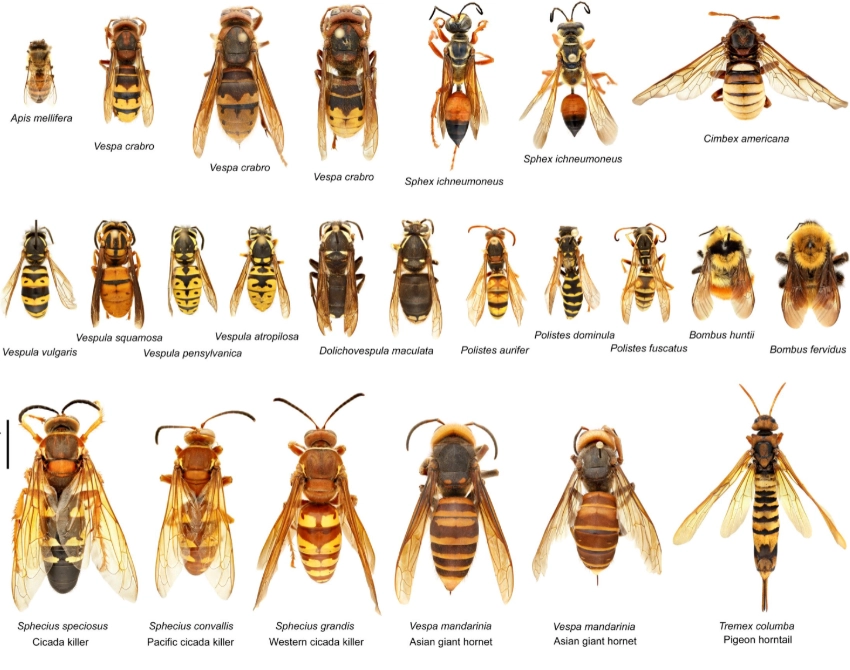

Step 4: Color & Pattern (But Be Cautious!). Note the colors and markings. A yellow and black insect could be a bee, a wasp, a hoverfly, or a beetle. Color alone is treacherous. Use it with the other features.

Step 5: Consult & Compare. Now take your notes and photos to your resources. Use the app. Search BugGuide by the features you saw. Don't jump to the first result. Look at multiple images. Read the descriptions. Does the habitat match? Does the size range fit?

Meet the Common Cast in Your Garden

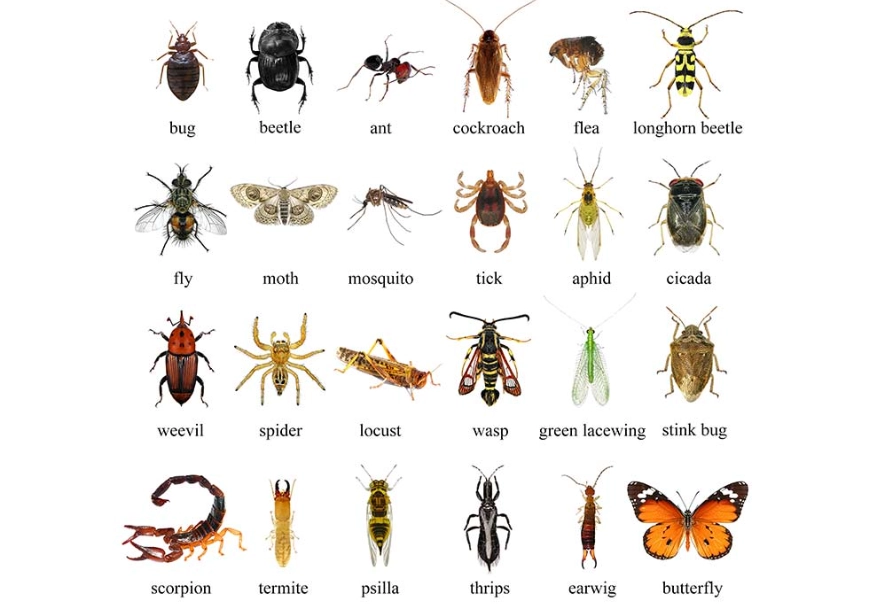

You'll see these characters repeatedly. Knowing them by sight saves time.

| Insect (Common Name) | Key Identifying Features | What It's Doing | Friend or Foe? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ladybug / Ladybird Beetle | Dome-shaped, usually red/orange with black spots. Larvae look like tiny black & orange alligators. | Adults and larvae voraciously eat aphids. | Friend. Protect at all costs. |

| Hover Fly (Syrphid Fly) | Looks like a small bee/wasp but has only two wings (bees have four), huge eyes, and hovers in place. | Adults pollinate; larvae are aphid predators. | Major Friend. Harmless mimic. |

| Ground Beetle | Long legs for running, often shiny black or iridescent, with grooved wing covers. Fast-moving on soil. | Night hunter of slugs, caterpillars, and other soil pests. | Friend. A nocturnal guardian. |

| Japanese Beetle | Metallic coppery-green body, white tufts of hair along its sides. Often found in groups skeletonizing leaves. | Feeding on roses, grapes, linden trees, etc. | Notorious Foe. Destructive pest. |

| Earwig | Slender, brown, with pincer-like cerci at the rear. Hides in damp, tight spaces during the day. | Omnivorous scavenger. Can damage seedlings but also eats some pests. | Mostly Neutral. Manage if numbers are high. |

The Quick & Dirty "Friend or Foe" Test

When in doubt, ask these questions fast:

- Is it chewing holes in the leaves/flowers/fruits I want to keep? If yes, potential foe. Get a closer ID.

- Is it hanging around aphids, scales, or other soft-bodied pests? It's likely a predator (ladybug, lacewing, hover fly larva) or parasite (parasitic wasp). Friend.

- Is it visiting flowers? Probably a pollinator (bee, butterfly, fly, beetle). Friend.

- Is it fast, predatory-looking, and not damaging plants? (Like assassin bugs, spiders, ground beetles). Usually a friend keeping other pests in check.

This isn't perfect, but it stops most knee-jerk squishing.

Top 3 Mistakes Beginners Make (And How to Avoid Them)

I've helped hundreds of people with IDs. These are the consistent slip-ups.

1. Over-relying on color. This is the biggest one. I mentioned the yellow-and-black trap. Also, many beetles mimic bees. Many harmless flies mimic wasps. Color is a suggestion, not a diagnosis. Focus on wing count, antennae shape, and body structure first.

2. Ignoring the immature stages. A butterfly is not just the pretty adult. The caterpillar, the chrysalis—they're all part of its life. That "ugly" brown grub in your compost is likely a beetle larva, not a "bad worm." That spiny, colorful thing eating your dill is a black swallowtail caterpillar, a future pollinator. Learn to recognize common larvae and nymphs.

A Personal Story: I once spent an hour trying to ID a "strange fly" in my garden before realizing, with embarrassment, it was the adult form of a hover fly whose larvae I'd been celebrating for weeks. Life cycles matter.

3. Not noting the habitat. You won't find a diving beetle in a dry field. You won't find a periodical cicada nymph above ground most of its life. "Found on a milkweed plant" or "under a rotting log" cuts the possibilities by 90%. Always include location and habitat in your mental notes or photo captions.

Your Insect ID Questions, Answered

What's the fastest way to identify an insect I just found?

How can I tell if a caterpillar in my garden is going to be a moth or a butterfly?

I found a bug in my house. Is it a bed bug, and what should I do?

What's one feature most people overlook when trying to identify flying insects?

The next time you see an insect, don't just see a bug. See a puzzle with six legs. Grab your phone, take a breath, and start with the big questions: Where is it? What's its body like? You've got the steps now. Go be a detective.

The next time you see an insect, don't just see a bug. See a puzzle with six legs. Grab your phone, take a breath, and start with the big questions: Where is it? What's its body like? You've got the steps now. Go be a detective.